About

About

Bob's Obituary

In December 1995, the Canadian Folk Music Bulletin published a retrospective interview on my life and times in folk music called "That's what folk songs have always done....". I call it "My Obituary". The following are exerpts. A section on the making of Sulphur Passage and another on my favourites among my songs appear elsewhere on this site. Even then, there are sections I have left out. (God, it was a long interview.) If you want to read the whole thing, get in touch. Thanks to George W. Lyon, John Leeder and the Canadian Society for Traditional Music.

Bob defines folksinging

CFMB: Since you are a banjo player known for your political songs, it seems a good guess that Pete Seeger has been a big influence on you.

What I do is similar in many ways to what Pete has done, but I don't do what I do because he did it. Undoubtedly the path is easier for me to go down because he cleared the trail. But I never modelled myself after Pete. I don't see much similarity in our music. There is more similarity in our subjects, and even more in what we don't take for our subjects. He didn't write and sing because there was a market niche for some song or subject and neither do I. We're folksingers, he long before me. And there are not a lot of modern folksingers, at least by my definition.

Which is?

Folk music is the music that rises naturally from a community. As a definition, that may not be airtight, but I see it like this: Making music is an absolutely natural thing to do, as natural as running, as natural as speaking. I can sure see that in my two-year-old. People just sing. And left to our own devices, we'd sing about anything we'd talk about. People have always sung their protests, just as they have sung their love. They made up songs about their friends. About tragedies, controversies, work. They made up songs for weddings, played tunes for the dance, made up a ditty and dedicated it to someone for a birthday. If people in the community were talking about something -- cutting down a forest, putting in a highway -- they sang about it too.

But that natural music-making dropped off as the music industry took over and inserted itself between the makers of music and the consumers of music. Songs became commodities you purchase pre-fab. In order to have music, we think we have to pay Sony. We think real music is something you buy a ticket to hear. They hooked us, made music slick and mass-produced, and replaced the music that comes naturally. But the natural thing is to be singing in our own way about our own subjects, including lots of subjects that now get weeded out by the censorship of the marketplace.

That's what folksingers do; they still sing those other songs. That's what Seeger has done, and that's what I do. We're throwbacks. We are professional folksingers, which is almost a contradiction in terms, though not quite. Because while we do sing for money, we don't create the stuff for the money. If I wasn't being paid I would still write and sing pretty much the same songs. I don't think "Oh, here's a song that could really get popular" or "Here's a song that I could sell to so-and-so." I know there are people that write that way. In fact, they write some really nifty stuff. But I'm not one of them. I write about the things on my mind, which are the things on the minds of people in my community.

How Bob got that way

What got you started in music? What got you started as a career musician?

Like I say, singing was like breathing. I just sang, we all did. My dad used to sing as he walked around the house, and my mom did too. I was also raised around show business. My dad was a booking agent, booking acts into night clubs in southern Ontario. We went out to lots of clubs and shows, and my dad would bring the entertainers home for a meal. So show business was a pretty natural milieu for me.

I started performing in school shows as soon as I was old enough to do it. I did imitations - Ed Sullivan and the like. And took great joy in it. You see, I was a terrible athlete; maybe that's why I started to perform. It was something I had a knack for, as opposed to catching a ball, for which I had no talent at all.

So that was the beginning. Playing music came later. In fact, I got Ds in music at school. But I listened to music, the pop of the day. The radio in the kitchen would play, "Hummin'bird, hummin'bird, sing me your song" and "The wayward wind is a restless wind" and "Have you talked to the Man upstairs, 'cause he wants to hear from you?" - pre-rock-n-roll pop music.

He discovers rock and roll

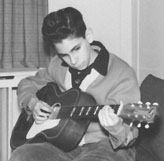

Then - I think it was 1954 - the radio changed and, all of a sudden, there was "Rock Around the Clock" by Bill Haley & The Comets, and shortly after that, the early Elvis records. And, boy oh boy, they were something! They just rocked, they touched me, they were rebellious. I wanted to be like Elvis and, at the age of 9, I asked for a guitar. I didn't get an electric guitar, because you needed an amplifier too, and my parents didn't want to spring for it. They thought I wouldn't stick with it. So I got a $20 Serenader.

That's where it started, rock and roll on the radio and G, C and D7 on the top three strings of the Serenader. I begged my dad to take me to the touring rock and roll shows that came through Toronto. I saw Fats Domino, Gene Vincent, Buddy Holly, The Platters, Elvis.

But then, very quickly, as I recall, rock and roll turned bland. For maybe three really good years, it was wonderful, raunchy, rebellious music - Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis, people like that - and then suddenly it was "Sixteen candles make a lovely light, but not as bright as your eyes tonight." Industrialized music pitched to a generic teen market. Pat Boone singing "Long Tall Sally" in a squeaky clean voice.

He hears Tom Dooley

Then in '59, when rock and roll was at its nadir, I heard "Tom Dooley." It stopped me in my tracks. This was a song that seemed to be about something. Was it a true story? Were these real people? I was fascinated. Musically, as sung by the Kingston Trio, it was, shall we say, plain. But it hinted at a story, and I wanted to know the story.

So I went to see the Kingston Trio when they came to town, and, during the show, they said, "There's a group coming up that you are going to hear a lot about, called Peter, Paul and Mary." And, sure enough, a few months later, Peter, Paul and Mary came through. They were certainly a step up, musically. From there it was a short step to Ian and Sylvia, whose music, particularly on their early records, was pretty much timeless - it still stands up today. They opened the door into real, not-commercialized folk music. People like the Reverend Gary Davis. If they passed through Toronto, I went.

So I fell into folk music. It was really very easy to do because it was this unique moment in music history when folk was a craze. It had little to do with the actual folk elements of the music, and was probably anathema to it, but folk was on the radio and in the clubs. So there was a sea of folk music to swim in, and I did. I stopped listening to pop music and never really started again.

He ignores his mother's advice and chooses a career in folk music

How did you get into music as a career?

The real impetus was political. In the late 60s, early 70s, so much was happening all over the world. The Viet Nam war was on. Paris, Prague, Columbia University all exploded in '68. The same year, Rochdale College opened in Toronto. (That's a story in itself.) The killings at Kent State were in '70. Canadian campuses were less turbulent - we are Canadians after all - but it was probably the most exciting moment of the century to be around the university, and I just had the luck to be there. We really thought we could change the world. We were naïve, but in our naïvety we threw ourselves into the biggest issues of the time with all our passion and energy. It was a wonderful time to be 20 years old.

At the same time, the hippie culture flowered, and the hippies, whatever else they represented, were people who, like the young radicals, certainly rejected bourgeois values. So I found the hippie culture exciting too - though I was never innocent enough to be a dyed-in-the-wool flower child.

The hippies brought with them a whole new batch of music. Music was sacred to that movement - as it is to all political movements. Everything from the Beatles (who were like a singing advertisement for LSD), to the Jefferson Airplane ("We are all outlaws in the eyes of Amerika"). The music wasn't just music, it was the voice of our rebellion.

And I thought, in 1970 (at the ripe old age of 24), if I have a gift, it is to take ideas and cast them into plain language. So I thought I saw a useful, socially-responsible role for myself: I could use folk music to express the alternate, counter-culture, socialistic vision a bunch of us seemed to hold in common and, in that way, reach young people already keen on changing the world. Naïve as hell, but there is also something sweet and admirable in that seriousness of purpose.

And, as it turns out, that is precisely what I've done. It has proved to be enormously more difficult than I thought. I have influenced a lot fewer people than I dreamed about. I think had I known how tough a road it was going to be, I might have been wise to choose a different career. But in fact my path has been straight as an arrow.

Stringband and Canadian nationalism

Back in the 1970's when Stringband was in its heyday you used slogans like "thoroughly Canadian" and "God save The King". There was a twinkle in your eye, but were you also consciously trying to represent Canadian culture in song?

Absolutely, though the consciousness grew out of the experience, it didn't precede it. I always liked something Doug Fetherling said about Stringband in Saturday Night magazine, back before it became the right wing rag it is today. Fetherling said, "They search relentlessly for what they think is a Canadian Sound. Not finding it they have perhaps invented it." We definitely did set out to find and write and sing songs that reflected the particular lives of people in different corners of the country. That was a unique thing to do back then. I like to think that we helped clear the path for those who are doing it now, and there are a lot of them. By singing Dief Will Be the Chief Again we opened a door, we gave a kind of permission to sing about our own particularities.

Of course in some ways the border between the US and Canada is a false distinction as far as music goes. The rise of sheet music had the same effect either side of the border. Or the rise of the player piano or of radio - the various industrial interventions that turned music into a saleable commodity. The commercial society, the capitalist society, has marginalized folk music, the natural music of a community, both sides of the border. In fact community itself has been marginalized. We - Stringband - just went back there for our music. The particulars were Canadian because we were.

Bob reflects on the state of the nation yet still finds a reason to believe

You mention community a lot. How do you define community?

That's a good question, and I don't have a neat answer. But in practice, I suppose I define community as people with shared interests they hold separate from and, indeed in spite of, the onslaught of commercial and political propaganda raining down on us.

We live in a time and in a society that must be one of the most heavily and most successfully propagandized in history. There is so much pressure to disavow our own communities' needs and experience (and indeed our own personal needs and experience) and substitute the proscribed attitudes churned out by the centre of money, power and mass communications.

For instance, these days many people, maybe even most people, really believe that the country is broke. We have been told that so often. We can't afford medicare, or unemployment insurance, or battered women's shelters because we're broke. It's propaganda, a posture. It has nothing to do with our own experience. Just look around. Walk down Bloor Street in Toronto, 4th Avenue in Vancouver, walk through Kensington in Calgary, then tell me the country is broke! We are rich as Croesus. As a society, we can afford VCRs, handi-cams, CD players, cable TV, the Blue Jays, The Phantom of the Opera - but we can't afford medicare? In Ontario they reduce the income of welfare mothers to "fight the deficit," and then give a tax break to people who are better off to "stimulate the economy." It takes a powerful load of propaganda to make people swallow something so obviously contradictory, so openly self-serving. But the propaganda is incredibly pervasive. It is damn hard not to be taken in, hard to trust your own experience and not substitute the "wisdom" of the rich, articulate guys in suits who dominate TV, radio and the press. I mean, Geoffrey Simpson looks knowledgeable, he sounds knowledgeable and he is saying the same thing they are all saying... if he thinks the emperor's new clothes are terrific, they must be.

But communities, whether defined by geography or shared concerns, do have their own real interests and histories. Stretched far enough, the veil of propaganda starts to tear, and those real interests, that real experience, comes back into focus. Inherent in the domination of public discourse by the rich and powerful is its antithesis, because in many ways we can feel that our own community values are just not there. I think the next few years are going to see a very exciting fight over the soul of the country. I am not a Pollyanna about this. The bad guys are winning. If they get their way, and they very well might, they could do such damage to the fabric of the country, the fabric of our communities, they could so Americanize us, that it will take generations to recover.

The same forces are at play when it comes to music. The entertainment industry juggernaut has certainly marginalized folk music, just as the political juggernaut has marginalized community itself - the source of folk music. Being a folksinger was never an easy job, but now it is harder than ever. The cultural organizations that have played an important part keeping non-commercial culture enterprises afloat - including folk singers - are being cut to the bone. Meanwhile the commercial entertainment alternatives, from watching videos at home to spending $100 to see Showboat, have never been more pervasive, more hyped. I seriously doubt whether Stringband could have kept going, had those days been like these.

And yet, and yet ... people like you and me, people who like the music, who like the heart it has, feel the absence. And given the opportunity, we will express our own community interest. That is what happened with GABRIOLA V0R1X0.

When I decided to record again, after being away from the studio for something like 15 years, I wasn't very confident. Would an album by an old folksinger get any play? Would there be venues where I could perform? Would I be able to sell more than 200 copies to die-hard old Stringband fans? To be confident would have been to be foolish. So I decided to fundraise. I set out to raise $5000. When the dust had settled, I raised $25,000! It was the single most rewarding experience of my working life. It was my Academy Award. Of course it was flattering; it is wonderful to feel that appreciated.

But I think something else was going on: I think people saw a chance to fight back against the system, against the music industry, to express solidarity with their own community's music. And as a result of their intervention, I was able to once again put out songs expressing the values we share. I was able to express my (and our) equivocal thoughts about marriage and parenting in these times. I was able to make a song out of our anger and hurt at the destruction of the wilderness - and our determination to stop it. And those expressions go back into the community, and strengthen it against the rain of propaganda. That's what I do. That's what folk songs have always done.

I think now, as I get older, it is my fate to remain fairly obscure, to be a marginal performer who has little impact on mainstream culture. What I do won't be the lead story in the entertainment section of The Globe, it won't get rotation on MuchMusic. I won't play the Glenn Gould Theatre or do a guest spot with Rita McNeill. Too bad. But I know how much effect my work has on people in my community, who take the energy of my songs and channel it into their work, and their work encourages someone else. That's the legacy of what I do, and that feels pretty good to me.